Perhaps the impetus to return to Annemarie Schimmel’s Mystical Dimensions of Islam came via someone posting a best-books on mysticism. Thanks to that person who gave the assist because Schimmel's book is heavy, imposing with its 500 pages and extensive footnotes. Her scholarship enriches every page, and this demands/invites careful reading—but well worth the investment. The depth of expertise provides guidance through the writings and the lives of so many seekers of truth. Facing this impressive work, it would be easy to take a passive stance; but instead Schimmel calls for active engagement to quest into the divine:

“In interpreting Islamic mystical texts, one must not forget that many sayings to which we give a deep theological or philosophical meaning may have been intended to be suggestive wordplay; some of the definitions found in the classical texts may have been uttered by the Sufi masters as a sort of ko’an, a paradox meant to shock the hearer, to kindle discussion, to perplex the logical faculties, and thus to engender a nonlogical understanding of the real meaning of the word concerned, or of the mystical ‘state’ or ‘stage’ in question. The resolution of apparent contradictions in some of these sayings might be found, then, in an act of illumination.” (pp. 12-13; cf Sells’ Mystical Languages of Unsaying)

Among the definitions of Sufism, Schimmel includes a gem from Rumi: “‘What is Sufism?’ He said: ‘To find joy in the heart when grief comes’ (Mathnawi 3:3261).” [p. 17; Nicholson translates “sorrow” in place of “grief” and references Q 57:23.]

One of the precious gifts of reading this book involves a deepened impression of the interconnection between approaching the Divine and participating in the praise of creation. For example, writing about Dhu’n-Nun (d. 859) and early Sufi mystics, Schimmel translates:

“O God, I never hearken to the voices of the beasts or the rustle of the trees, the splashing of the waters or the song of the birds, the whistling of the wind or the rumble of the thunder, but I sense in them a testimony of Thy Unity, and a proof of Thy incomparability, that Thou art the All-Prevailing, the All-Knowing, the All-True” (p. 46)

These meditations resonate with the tonalities vibrating from walking amid gardens and woodlands, open to photographic compositions, to close-up revelation of intricate design, to graceful flitting in of butterflies or falling leaves, and to the comforting remembrance

|

| Screensaver appearing alongside the draft as this was written. |

as treasured savings float onto the screen.

|

| Screensaver appearing alongside the draft as this was written. |

This participation in nature's manifestation, too, may be offered and realized as praise, as prayer, as presence.

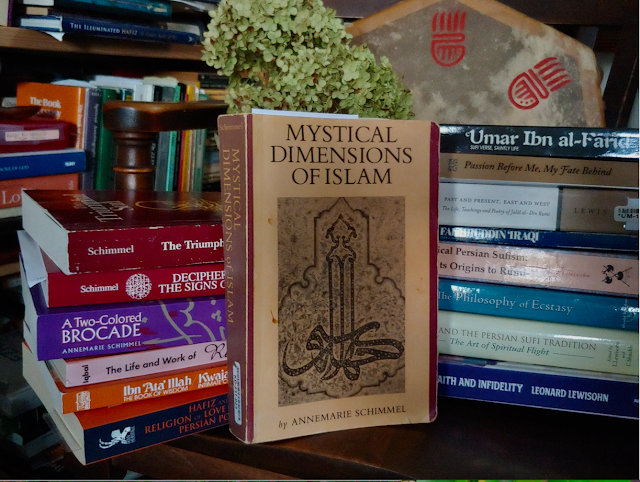

How many times was I tempted by Schimmel’s accounts of the mystics when she referenced their texts to take up one of those books from a shelf? A stack of them soon built up alongside my desk [see photo at top]. Now having completed Mystical Dimensions, should the next reading be another of Schimmel’s or Franklin Lewis’ much-praised Rumi or one of Lewisohn…?

Although I hope to engage each of those texts, it’s another she discussed that’s now bringing light: Sir Muhammad Iqbal's Javid-Nama (translated by Arberry). For example,

“… when yearning makes assault upon a world

it transforms momentary beings into immortals,” [p. 94, lines 2221-2222]

“Wherever you see a world of color and scent

out of whose soil springs the plant of desire

is either already illumined by the light of the Chosen One

or is still seeking for the Chosen One.” [p. 98, lines 2331-2334]